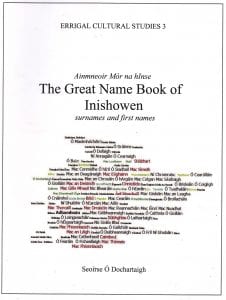

Origins and original Gaelic spellings taken from Seoirse’s book The Great Name Book of Inishowen. The author has delved deep into the Pardon Lists of 1602 & 1608 and The Hearth Money Rolls of 1665 in his quest for provenance and authenticity. Ancient genealogies also consulted.

The personal names and surnames of Inishowen go back many centuries. They cover every period of its history: from the Bronze Age to the historic period and right into medieval times. Gaelic families have left their imprint on the shape of many old names that are still in use to this day, although corrupted now through Anglicization.

A wave of Scottish Gàidhlig names expanded the range from about 1610 to 1700. Experts on the Plantation period tell us that after 1700 Presbyterian settlement in Inishowen was formed by internal movements rather than by further immigration from Scotland. Newer names that came to Inishowen after this period – of both the Scottish and Irish variety – obviously have roots outside the peninsula. In the case of Inishowen Scottish names, their presence there in the 1600s testifies to a long tradition of integration between the two countries, going back much further than 1610.

This book deals with names both of the personal and the surname type that the Gaelic peoples of Scotland and Ireland have passed on to us. The Scottish names are often heavily disguised as English-sounding names. Who would have thought, for instance, that the names Bell, Ewing, Colhoun, Boyd, Campbell, Wilson, Thompson, etc., were originally written in a Gaelic form? These had barely any resemblance to the modern forms. The Bells, when they first arrived in Inishowen, were called Mac Gille Mhaoil. The “bell” sound comes from the last part of this Gaelic name, pronounced “wheel”. Anglicisation can sometimes look like a deliberate process of cultural denigration.

The richness of the Gaelic imagination is plausible in all of the historic and prehistoric periods of the peninsula as regards to the naming of children. Unfortunately, this richness is not apparent in the choices of first names made during the 18th, 19th and early 20th centuries. There was a preponderance of names like John, Mary, James and Margaret and this reflects a sad loss of cultural self-esteem and self-worth that once characterized the peoples of Gaelic Ireland and Gaelic Scotland. Hopefully, readers will find here a better understanding of this older naming system and even discover some valuable source material for the current naming of children.